14. Enactive, Embodied Communication in Hermeneutic Healthcare - Part 2 (The role of touch)

In the last blog, I provided some definitions and introductory explanations of the model of enactive, embodied communication. In this post, I extend that thinking by talking about its relevance to healthcare, particularly healthcare which is oriented towards hermeneusis (sense-making) - and that which involves the therapeutic use of touch.

To recap, enactive, embodied communication is something that inevitably occurs when people are physically present with each other, through complex processes of intersubjective, interoceptive attunement, mutual action, and shared-sense making. It happens whether we are conscious of the process or not. It is the context for social cognition, and (I posit) is likely to be operative even when we are not in the same location as our sense-making partner (I am thinking of the role of FaceTime and Zoom in enabling lived body intercorporeity - a topic for an interesting research project!)

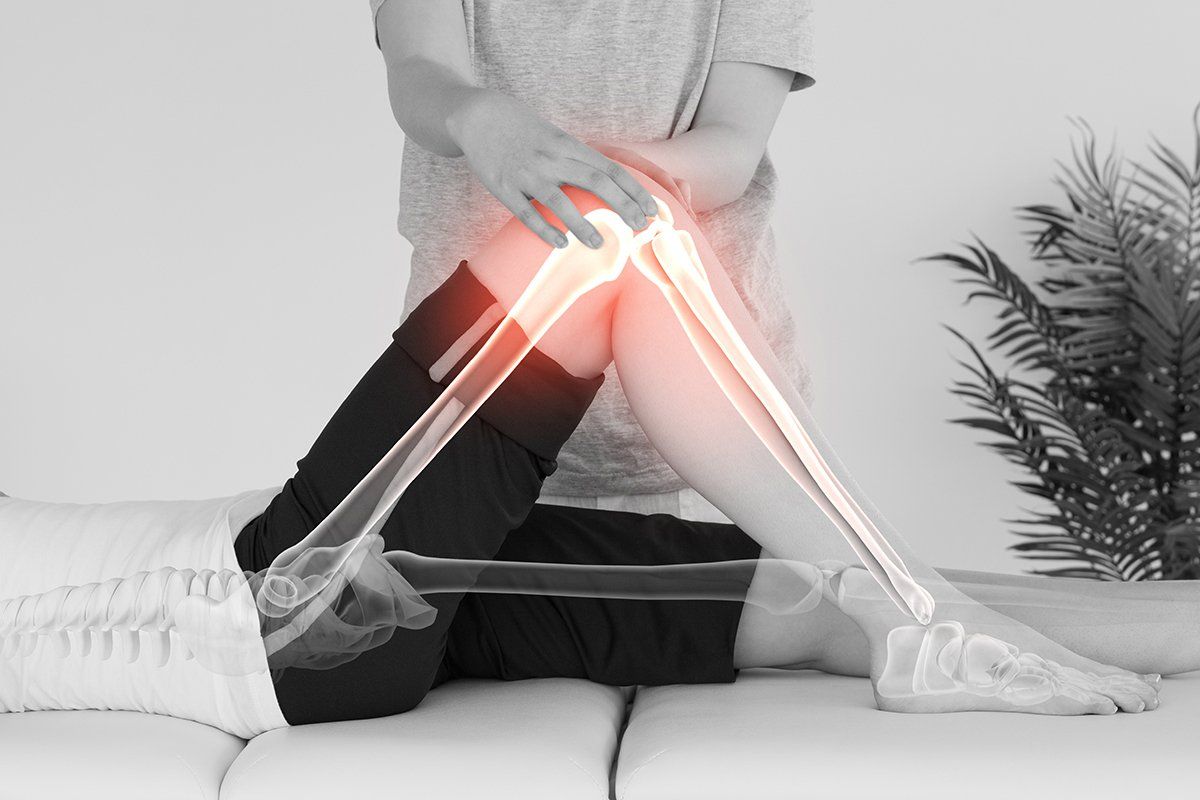

Enactive, embodied communication entails participatory sense-making, and when touch is involved, there is an additional modality of communication to take account of. Many philosophers of mind and consciousness use the modality of vision as representative of the entirety of our sensory engagement with the world. There are many ways in which the haptic senses, including those of interoception, kinaesthesia and proprioception, differ from the modality of vision, and it is interesting that touch is often left out of accounts of participatory sense-making and enactivist theory.

Maurice Merleau-Ponty was fascinated by the way we use touch to blend with the world in a fleshly way. And philosopher Susan Stuart (2016), in her reading of phenomenologists Merleau-Ponty and Eugene Gendlin, proposed a model for participatory communication via touch, after encountering the work of French cranial osteopath, Emmanuelle Roche. Stuart related Roche’s description of cranial osteopathic palpation to Merleau-Ponty’s ideas of intercorporeity, using the novel term “enkinaesthetic entanglement” to portray the reciprocally felt experience of understanding that occurs without linguistic articulation when touch is used in the process of sense-making.

Roche describes the palpatory experience of cranial osteopathic touch as an activity in which osteopath ‘listens’, ‘attends’ and ‘observes’ the interior of their patient - through a light palpatory contact - both the harmonious and discordant rhythms of the micro-movements that animate the patient’s whole body, such as “la croissance des cheveux, l’intérieur des viscères, le jeu des systems musculo-nerveuex et intraveineux” (the growth of the hair, the interior of the organs, the play of the neuro-muscular and intravenous systems) (Gens et Roche, 2014, p. 5).

Stuart (2016) portrays this form of sensory engagement as a “synaesthetic listening-feeling process, the gentle touch - and even non-touch - of palpation listening for rhythms and arhythms”, characterised by non-striving receptivity and “an openness to what presents itself” (ibid., p. 27). Referencing Merleau-Ponty, she claims that this manner of cranial osteopathic intersubjectivity is “first and foremost an enkinaesthetic intertwining, a circle of the touched and the touching and what comes to light, that is, what is brought forth through the feeling shifting somatic sense” (ibid., p. 27).

In my next post...

Part 3 of Enactive, Embodied Communication in Hermeneutic Healthcare, I will consider the role of participatory sense-making within hermeneutic healthcare further, expanding beyond the current example of cranial osteopathic palpation.

You might also like...